- These figures do not compare like with like – either in terms of what is being measured, or when those measurements were taken.

- There is no single, universal definition of child poverty. When comparing poverty rates in different places, it is crucial to ensure that the same definitions are being used, and that all data covers a similar period of time.

- While there is robust evidence that child poverty is higher in the UK than it is in the Scandinavian countries, the difference is nowhere near the degree suggested in this claim.

On 26 March in a post on social media, BBC NI journalist Mandy McAuley made a claim about recent child poverty figures in the UK compared with Scandinavia:

“#ChildPoverty

Denmark 2.4%

Finland 3.2%

Norway 3.6%

Sweden 3.6%

The UK 28.3%”

This is inaccurate.

Although child poverty in the UK is considerably higher than it is in the Scandinavian nations, the figures quoted here are not comparable. They involve several different definitions of child poverty and do not cover the same periods of time.

Ms McAuley spoke with FactCheckNI about this and she was in clear agreement with our assessment, which she said was an honest mistake. She told FactCheckNI:

“I thought these were recent figures and a fair comparison. It was a genuine mistake and I have now deleted the tweet.”

That original tweet was deleted this week – but Ms McAuley maintained a record of it on social media, in order to highlight her mistake and correct it.

Everyone can (and will) make mistakes – but not everyone reacts to those mistakes in the same way. FactCheckNI would like to say explicitly that this is an exemplary response to making an error.

But why was it a mistake in the first place?

- Definitions

There is no single, universally-accepted definition of child poverty (or even simply poverty). Instead, different organisations, groups and even nations will tend to use different measures over time.

Absolute poverty and relative poverty are two separate concepts (see this previous fact check for a more detailed explanation) and beneath those two umbrella definitions are many different ways to qualify or quantify measures of poverty.

In the UK, child poverty is often measured by comparing household income set against a particular threshold (see this explanation from the Children’s Commissioner) – usually either the median net household income for the year of measurement or the median net household income in 2010/11 Children growing up in a household whose income is below 60% of this income are said to be living in “relative” poverty (in the former case) or in “absolute” poverty (in the latter).

Another common dividing line for different ways to look at poverty is whether household income is considered before or after housing costs.

Globally, “child poverty” has a quite different definition: UNICEF, for example, uses the common international definition of living below $2.15/day (or $3.65 per household in some definition). The World Bank expands this to a potential $6.85 in some circumstances. This is largely irrelevant to current comparisons of Western countries.

For Western countries, the OECD defines “child poverty” as “below 50 per cent median of the particular net equivalent income of the country”.

Ultimately this means there are many different, usable definitions of child poverty for any given time period. When directly comparing child poverty rates in two different places, it is vital to ensure the figures in question stem from the same definition and same period of time.

- Figures

The many different definitions of child poverty, and the many different organisations tracking these different figures, can make it tricky to isolate and identify specific statistics.

FactCheckNI searched thoroughly to find measures of child poverty that matched the percentages applied to Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden in the original claim. The only matching dataset we could find can be seen here, in an article in the Guardian dated from 2009, quoting figures from UNICEF.

Furthermore, those quoted figures define poverty as living in a household with income that is under 50% of the national median. The UK figure from that same chart is 16.2% (rather than 28.3%) although the main issue with this data is that it is at least 15 years old.

- What about the UK figure?

FactCheckNI could not find any good data suggesting child poverty rates in the UK were at 28.3% (although that does not mean such data does not exist, given the wide range of different ways to measure child poverty – if you know of any such figures, please get in touch).

A report for the Centre for Social Policy at Loughborough University, which had it at 28.3% in England in 2014/15, though this had since in fact risen (see Figure 1). It should be noted that this figure is specifically after housing costs, with the poverty rate before housing costs significantly lower.

However, figures from the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) in its analysis Households Below Average Income: an analysis of the UK income distribution, published last August, indicate that 29% of children in the UK are living in relative poverty (defined as living in a household with income under 60% of the national median, after housing costs (the figure for poverty before housing costs in the same report is 20%). This is similar to, but not exactly the same, as the UK figure in the original claim.

- A better comparison

To compare child poverty in the UK to other parts of the world, it’s important to compare like with like – both in terms of what is measured, and when.

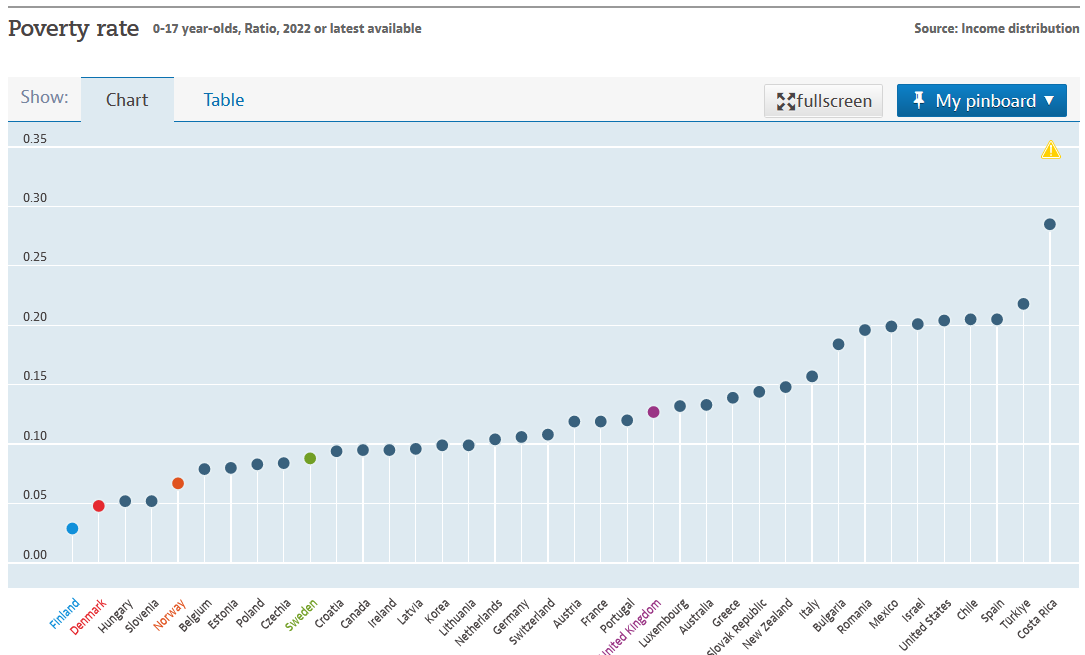

The latest OECD comparisons – with child poverty defined as “below 50 per cent median of the particular net equivalent income of the country”, and using data from 2022 and beyond – suggests child poverty in the five relevant countries as 2.9% for Finland, 2.8% for Denmark, 6.7% for Norway, 8.8% for Sweden and 12.7% for the UK.

Figure 1 – source: OECD data explorer

This does suggest that child poverty is a considerably larger issue in the UK than it is in Scandinavia, but not the degree suggested in the original claim.

Fundamentally, that claim did not compare like with like and, as such, is inaccurate.