- Abortion only recently became legal in NI, but stats from the last two decades in England and Wales provide no real evidence to support this claim.

- Official figures indicate that abortion rates have risen and domestic abuse has gone down. However, rates of wider sexual violence follow no clear pattern, and data around contraceptive use is less robust.

- Wider research from around the world is not definitive, but at least one peer-reviewed study found that experiencing domestic violence increases the chance a woman will have an abortion – as opposed to abortion access increasing the risk of abuse.

On 7 June on BBC Radio Ulster’s Good Morning Ulster programme, Bishop of Derry Donal McKeown claimed:

“The problem is that we find as abortion and contraception has been more readily available in society, domestic and sexual violence has increased.”

The suggestion is that increased ease of access to abortions and contraceptives has led to an increase in domestic and sexual violence.

Abortion has only been legal in Northern Ireland since 2019, and services were first commissioned in 2021, providing little data to examine over a short time frame.

Instead, FactCheckNI looked at trends in England and Wales over the past two decades and found nothing to support the Bishop’s claim. Over that time, domestic abuse rates have actually fallen, while abortion rates have risen.

Research from elsewhere around the world indicates a complex relationship between domestic abuse and violence and access to abortion and contraception. At least one study indicates that experiencing domestic violence makes a woman more likely to have an abortion (rather than the other way round).

This is an extremely complicated and important topic. As part of its process, FactCheckNI welcomes any and all additional sources of good information. If anyone knows of further information that could significantly add to this fact check, please get in touch.

UPDATE: This article was amended on 18 October 2023 with new information shared with FactCheckNI regarding possible links between domestic abuse and abortion. This information tallied with the evidence that we had gathered ourselves and, as such, does not alter the conclusions or rating on this fact check – although we want to make clear this info was both important and useful. More details can be found below in the ‘Other research’ section.

- Claim

Over the summer, FactCheckNI received several requests to look into this claim. We got in touch with Bishop McKeown to ask him where he got the information to support what he said.

The Bishop responded to us quickly, saying that he got the information in a newspaper, but couldn’t remember which one:

“I had actually read it some months ago in an opinion piece in a newspaper – and I don’t even remember exactly where. But the assertion had stuck with me.

“I really should have said on radio that I had read that claim but could not vouch for it. That is a lesson to be learned!”

FactCheckNI have been unable to locate this assertion in newspaper articles available to search online (but if anyone could point us to the article in question, that would be greatly appreciated).

Before we get stuck into our research and analysis on this issue, there’s also a lesson for everyone here. TV and radio, particularly live broadcasts, are understandably more chaotic than written articles because people don’t have the time to edit everything they say nearly as precisely. (FactCheckNI has written about this before.) That’s something to bear in mind when consuming different forms of media.

- Local data

FactCheckNI has assumed “readily available” abortion and contraception to mean legal and commissioned services that users can access relatively easily.

In Northern Ireland, abortion services were decriminalised in 2019 and commissioned in 2021, meaning there is little data to assess the claim.

In England and Wales, contraception was legalised in 1961 but only made readily available through the NHS in 1967 via the Family Planning Act. In the same year, abortion was legalised under certain criteria via registered practitioners by the Abortion Act, which properly came into force in 1968.

However, simply looking at trends in rates of domestic abuse in England and Wales since 1968 won’t adequately test the claim, for several reasons.

- Data issues

When it comes to domestic and sexual violence, there is one major problem with all available data: under-reporting.

Domestic abuse support charity Living With Abuse (LWA) estimates that currently an average of 35 assaults take place before a victim/survivor calls the police.

Under-reporting not only casts doubts on today’s domestic abuse statistics; it also makes comparisons between different times difficult because the scale of under-reporting may have changed over time.

Another issue is the shifting nature of what is considered abuse and/or a criminal offence. Marital rape has only been illegal in the UK since 1992. Until the Domestic Abuse Act 2021, which created a statutory definition of domestic abuse that includes coercive control, there was no specific offence of domestic violence or abuse. Instead, UK law addressed different forms of abuse and/or violence under different legislation.

There have also been changes in how crimes are recorded by police. A National Crime Recording Standard was introduced in April 2002.

For the reasons above, this check looks at data from 2003 onwards, providing almost two decades of statistics. It uses National Crime Survey data (rather than police statistics only) because this combines police figures with self-reported survey data.

- Contraception use and abortion access

Obtaining reliable figures for overall contraceptive use is tricky given people can purchase condoms easily, while other contraception is available via both sexual and reproductive health services and primary care.

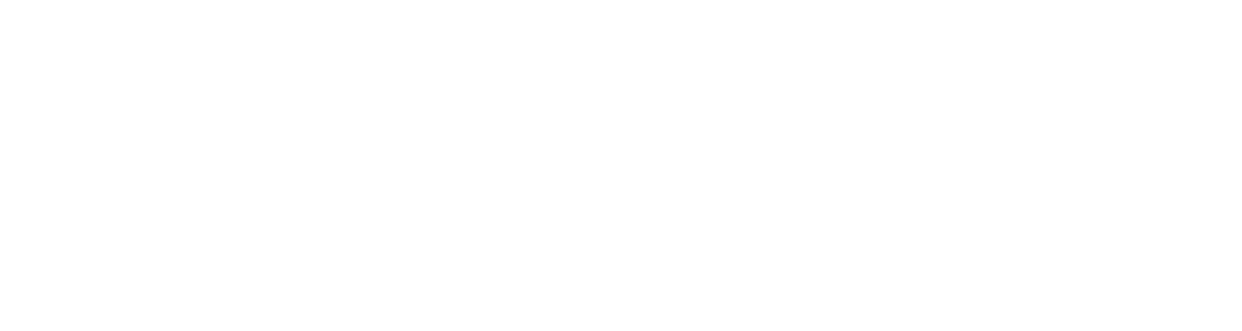

Research published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in 2021 looks at trends in non-barrier contraceptives (so not including condoms, diaphragms, cervical caps, spermicides or similar) in the UK between 2000 and 2018, and found a small decline in use overall – and from 2015 onwards, in particular:

Figure 1 – source: BMJ Sexual and Reproductive Health Journal

This might not amount to an overall reduction in contraceptive use but simply that increasingly people are using non-prescriptive options. Regardless, the change in prescription contraceptive use amounts to a couple of percentage points.

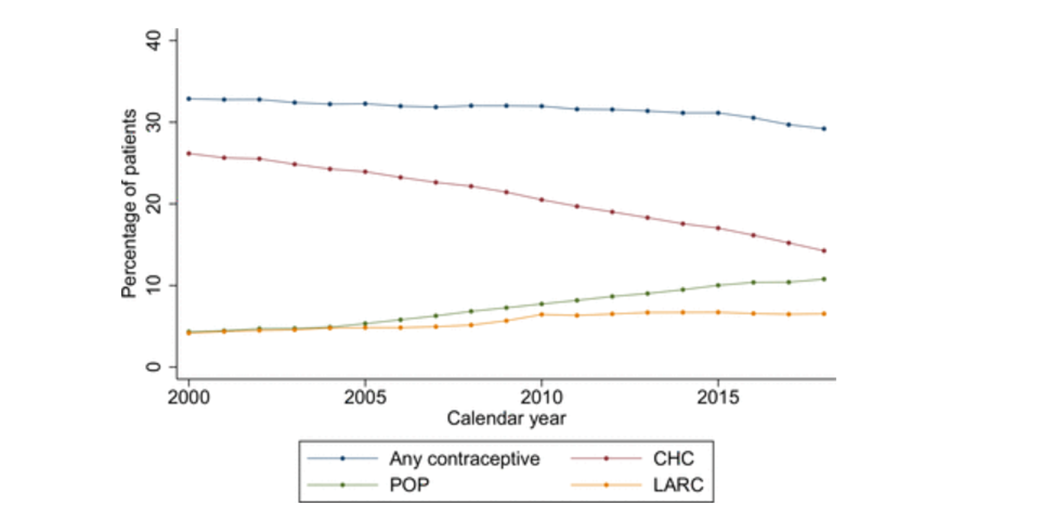

Abortion rates between 2001 and 2021 in England and Wales have broadly increased, according to official statistics, although the pattern involves a dip between 2009 and 2015, when rates began to grow once more:

Figure 2 – source: compiled from data from the Department of Health and Social Care, and the National Archives

- Domestic violence and abuse

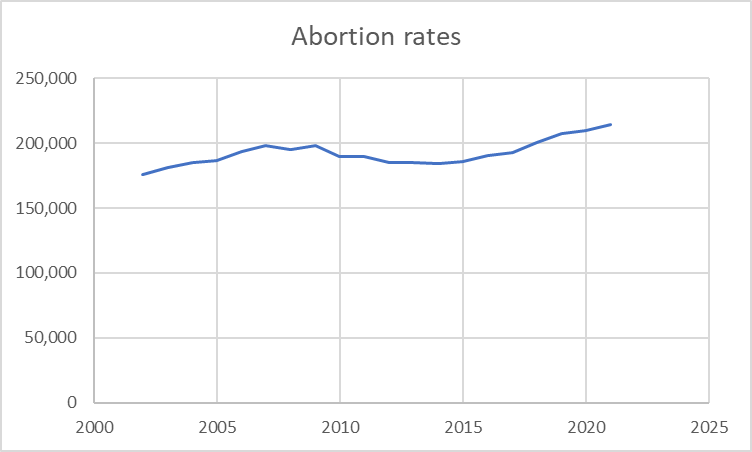

Office of National Statistics (ONS) figures indicate that reported rates of domestic violence and abuse, involving adults aged 16-59, fell significantly between 2004-05 and 2021-22.

Figure 3 – source: ONS

In particular, as the graph shows, the overall fall in domestic abuse seems to be driven by a fall in partner abuse throughout this time.

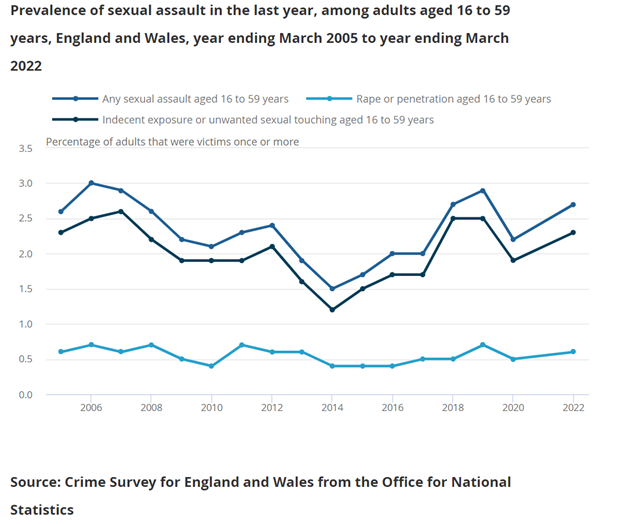

Looking at wider rates of sexual violence, an overall trend is harder to identify. The following figures cover the period from 2004-05 to 2021-22 but, while overall rates might be lower from 2013-14 onwards, the years ending March 2018, March 2019 and March 2022 were some of the worst over the past two decades.

Figure 4 – source: ONS

- Inferences

What does all this data imply?

Based on the data, it seems fair to say that abortion rates have grown and rates of domestic abuse have reduced. It is harder to identify any pattern in rates of contraceptive use or in indicidents of sexual violence in general.

However, there is a difference between correlation and causation.

Even if there is a seemingly-identifiable correlation between increased access to abortion and a reduction in domestic abuse, it does not mean that one causes the other.

Bishop McKeown’s claim implies that making access to abortion and contraception easier causes an increase in domestic and sexual violence.

Official statistics for England and Wales make that seem unlikely given abortion is going up and domestic abuse is going down, albeit the figures for contraception and wider sexual violence follow no clear patterns.

Actually pinning down any causation, one way or the other, requires complex statistical analysis and probably (in the case of contraception, at least) more robust data.

- Other research

FactCheckNI searched for pre-existing research looking at the relationship between access to contraceptives and abortion services, and domestic abuse and sexual violence. This involves research based on data from different countries around the world (rather than just UK data).

Findings include that increased domestic violence is associated with more inconsistent contraception use (i.e. lower use, not higher), and increased chances of unplanned pregnancy and induced abortion.

That finding indicates a correlation. It does not say that abortions lead to increases in violence. However, this study suggests that causation points in the other direction, with increased domestic violence increasing the chances that a women may have an abortion.

At the same time, pregnancy is also associated with an increased risk of domestic abuse.

Other known indicators for domestic violence include that perpetrators of abuse and violence are themselves more likely to have been exposed to domestic abuse as a child, while systematic wealth inequality, drugs or alcohol problems, and a litany of other personal, familial and social scenarios may also be aggravated risk factors.

UPDATE: Last week [on 12 October, 2023], we received further information regarding this claim, specifically evidence provided to Westminster by the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children making suggestions for domestic abuse legislation in the UK.

This evidence, from June 2020, looks at some of the relationships between domestic abuse or intimate partner violence, and abortions.

The submission backs up the evidence found by FactCheckNI indicating that domestic abuse can increase the chance that a woman has an abortion. The submission states: “Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a risk factor for abortion all over the world. A WHO [World Health Organisation] multi-country study found that women with a history of IPV had increased odds of unintended pregnancy and almost three times the risk of abortion.”

The submission also outlines some ways in which coerced or forced abortions can themselves be domestic abuse.

This does not change the conclusions from our check. However, FactCheckNI is always grateful for any and all new information presented to us, especially on important topics like this, where pre-existing evidence isn’t always definitive.

- Conclusion

Based on all the above data, there is little or nothing to suggest that Bishop McKeown’s claim that an increase in access to contraceptives or abortion leads to an increase in domestic or sexual violence.

In fact, data from the last two decades in England and Wales suggests that, as abortion rates have gone up, domestic abuse has gone down. However, this is a correlation; it has not been subject to full statistical analysis; and data for contraceptive use and for wider sexual violence indicates no obvious patterns.

That said, even such a correlation – abortions up, abuse down – is enough to provide some evidence against the Bishop’s claim. What it does not do, is provide good evidence of a causation in the other direction, i.e. that increased access to contraception and abortion leads to lower rates of domestic abuse and sexual violence.

We also found other pre-existing, peer-reviewed works, including at least one study that indicates that intimate partner violence does make abortions more likely: “IPV affected woman’s physical and mental health, reduced sexual autonomy, increased risk for unintended pregnancy and multiple abortions” – causation, in other words.

Bishop McKeown did tell us that he had read something that supported his claim in a newspaper article, although he could not remember what paper or vouch for exactly what the article said.

For all these reasons, we consider this claim inaccurate with consideration.

This is an extremely complex and important issue. More evidence to either refute or support the claim might be available. FactCheckNI always welcomes the submission of further evidence ([email protected]), post-publication of any article, whether it validates or refutes our conclusion. If you know of any, please get in touch.