- Research shows that longer waits in A&E lead to more patient deaths in the 30 days after that hospital visit.

- By combining those research findings with NI’s waiting time figures, it is possible to make some estimates about the number of additional deaths resulting from longer waits.

- FactCheckNI’s own calculations led to similar results as those published by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine.

In an interview published on 21 January in the Irish Times, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine’s (RCEM) Vice Chair in Northern Ireland Dr Russell McLaughlin claimed:

“In very simple terms, there is strong evidence that indicates that in 2022, 1,434 people died as a result of delays in Northern Ireland’s emergency departments.”

This claim is backed by evidence.

It relies on research published in the Emergency Medical Journal (EMJ), which found that longer waiting times in Emergency Departments among patients who are subsequently admitted to hospital can lead to more total deaths among those patients in the following 30 days than would have happened otherwise.

By combining the findings from this research with publicly-available data on ED waiting times in NI, FactCheckNI was able to carry out some calculations that back up the RCEM claim.

- Research

FactCheckNI asked the RCEM what the “strong evidence” was for this claim. They pointed us to research showing links between delays to patient admissions to hospital from emergency departments (EDs) and increased rates of death.

That research, published in the Emergency Medical Journal (EMJ), found that delays to hospital inpatient admission for patients waiting over five hours results in an increase in patient mortality over the following 30 days.

In particular, two separate increased rates in 30-day mortality were observed – one for waits of between six and eight hours (the lower rate) and one for waits between eight and 12 hours (the higher rate):

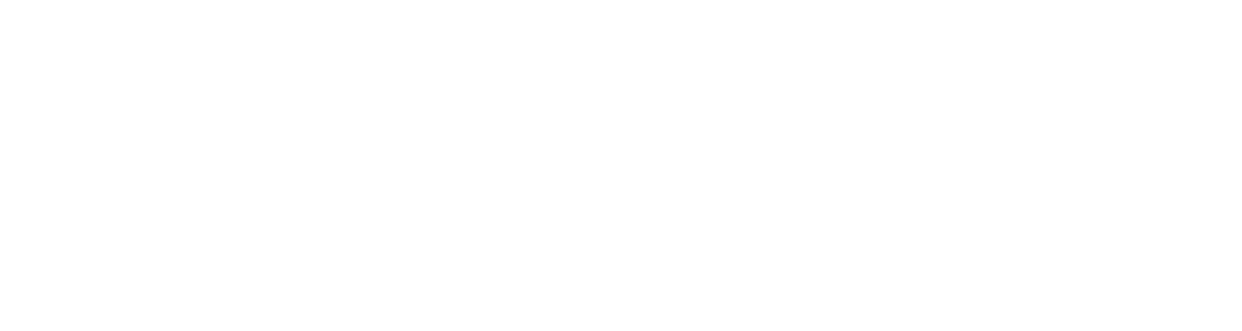

Figure 1 – source: EMJ

This table says that, for every 82 people waiting between six and eight hours in ED before admission to hospital, there will be one extra death in the next 30 days that would not have happened had the waits been shorter. Furthermore, the increase in mortality rate is higher again for longer waits: for every 72 people waiting between eight and 12 hours, there will be one extra death in the subsequent 30 days.

The RCEM said they used findings from this paper along with Department of Health figures on long waits in ED to estimate how many people died as a result in Northern Ireland in 2022.

- Calculation

The Department of Health’s quarterly bulletins on waiting times in ED do not routinely disclose all figures for extended waits among patients subsequently admitted to hospital (see the final section of this fact check for further details).

However, relevant numbers for 2022 are available from a recently-published ministerial response to a written question at Stormont:

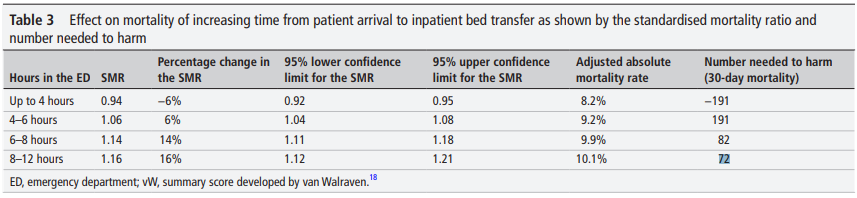

Figure 2 – source: Northern Ireland Assembly

So, in 2022 in Northern Ireland 106,761 people waited more than six hours in ED before being admitted to hospital.

This does not include a breakdown of how many people waited between six and eight hours, how many waited between eight and 12 hours, and how many waited even longer than that.

Given the findings from the research published in the EMJ (Figure 1, above), if FactCheckNI had a full breakdown of the number of waits that were between six and eight hours (call this A), the number of waits that were between eight and 12 hours (B) and also those that were longer than 12 hours (C) we could multiply those numbers by the relevant increased rate in mortality to calculate the total number of extra deaths.

Noting once more that the lower increased rate in mortality is one death for every 82 waits between six and eight hours, and the higher rate is one death for every 72 waits between eight and 12 hours, this calculation becomes:

A x 1/82 + B x 1/72 + C x 1/72

This calculation (which uses the extra death rate for the 8-12 hour cohort as the rate for waits of over 12 hours, in the absence of better information – more on that later) would lead to a robust estimate of how many extra deaths are likely to have emerged from long waits.

Instead, with only one statistic to work with (total waits of longer than six hours), what is possible are two different estimates – one likely to be an underestimate (using the lower rate of increased mortality) and the other an overestimate (using the higher rate).

- Estimates

Firstly, the underestimate, calculated by using the lower rate of mortality (one extra death for every 82 waits):

106,671 / 82 = 1,301 deaths in the subsequent 30 days, which is lower than the RCEM figure of 1,434.

Secondly, the overestimate:

106,671 / 72 = 1,482 deaths, which is higher than the RCEM figure.

Given that the RCEM’s figure sits comfortably between our underestimate and our overestimate, and the fact that the underestimate and overestimate are not wildly far apart, it is reasonable to conclude that this amounts to evidence that supports the initial claim.

That’s enough to say that the initial claim, bearing in mind the wider considerations, is accurate. However, there are several other aspects worthy of discussion.

- Excess deaths?

There is one area of possible confusion in what the RCEM is saying: excess deaths.

The RCEM’s website contains an outline of some of the findings of its research into extra deaths resulting from long waits in ED. That section is titled “Excess Deaths” and its introduction states:

“Using the best available evidence, a scientific study published in the Emergency Medicine Journal, we calculate an estimated number of excess deaths occurring across the United Kingdom associated with crowding and extremely long waiting times.”

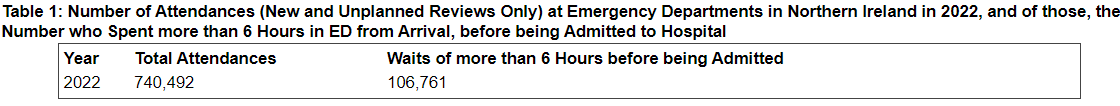

That section includes the following table, which outlines some of its own findings from its examination of deaths caused by long waits in ED – including the 1,434 figure for Northern Ireland – which it refers to as “excess deaths”.

Figure 3 – source: RCEM

The Irish Times interview discusses the ongoing state of emergency medicine in Northern Ireland more generally, and also touched on the issue of excess deaths.

The article says that the calculation that led to the central claim in this article – that 1,434 people died in 2022 as a result of delays in ED – was made “[using] what Dr McLaughlin describes as ‘robust’ research on excess deaths”.

Quotes from Dr McLaughlin include:

“I suppose the point is that we’re losing a significant volume of patients every year and it’s off the radar… Any excess death is a tragedy for the individual and the family but once you get into this level of statistics, you’re looking at systemic failure.”

The issue is that, technically speaking, not all of these will actually be “excess” deaths.

- Definitions

The calculations being made by the RCEM, and the research findings published in the EMJ, concern the fact that patients who wait longer in ED before being admitted to hospital have an increased risk of death over the following 30 days.

It is fair to characterise this by saying that lengthy or unnecessary delays in ED lead to deaths that wouldn’t otherwise have happened in the following 30 days, which could be called unnecessary deaths, or extra deaths or – in casual language – excess deaths. Indeed, that is the main point RCEM is trying to make.

However, the concept of “excess deaths” in health and social care has a different and clearly-defined meaning. Excess deaths are the difference between the observed greater number of deaths in a given period and the expected number of deaths in that period, based on historical data and trends. (FactCheckNI looked at excess deaths in detail during the COVID pandemic.)

The House of Commons Library published a paper in January looking at recent trends in excess deaths, while in February the Office of National Statistics (ONS) published an explanation of changes in methodology for calculating excess deaths in future (essentially using weighting adjustments and other statistical tools in finer detail, to try and improve comparisons between different years).

What is the issue with the RCEM’s work?

- Expected

While trends in excess deaths can be used to look at whether there are issues (one or several) leading to a number of unnecessary deaths, this isn’t what they actually measure.

Instead, excess deaths are calculated by using statistical analysis to compare the number of deaths in a given time period with the equivalent period over the previous five years.

The reason the extra/unnecessary deaths identified by the RCEM are not all excess deaths, in this sense, is because long waits in ED have not just sprung from nowhere. This has been an issue for years and, as such, a significant number of deaths resulting from long waits in ED will be included in death numbers from previous years and are therefore expected, rather than excess, deaths.

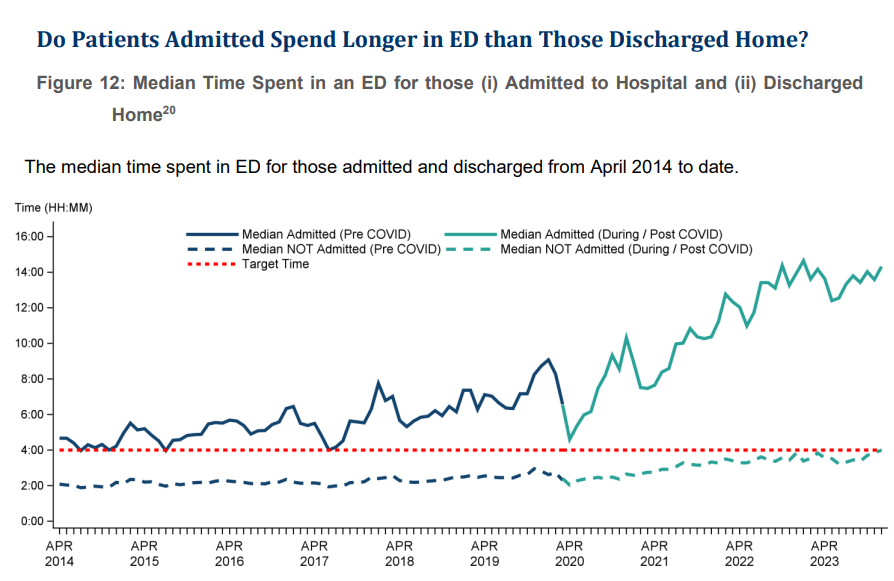

The number of long waits in ED is growing – see Figure 4, in the section below – which means a number of the more recent deaths would be defined as excess deaths, but not all of them.

This is not to suggest that the RCEM hasn’t identified a serious issue. The fact that some of these extra/unnecessary deaths are not excess deaths, statistically speaking, does not mean this isn’t a matter of huge concern – it just means this has been an issue for so long that, to some degree, it is now expected.

FactCheckNI pointed out this confusion in communication to the RCEM, who agreed with our analysis and said it would be more accurate to say that these long waits are associated with excess mortality.

The RCEM also made clear that its central point was that longer waits result in higher mortality, and that this is true whether or not those extra deaths technically qualify as excess or not.

“It is true that Northern Ireland had long waits before 2018 and that there will have been deaths related to these long stays beforehand… the distinction as whether these are ‘excess’ or ‘expected’, seems moot when long stays are modifiable. However, we really don’t think there is any justification for leaving people in emergency departments beyond five hours.”

And, while it is true that not all extra deaths from long waits will count as excess deaths, some of them will. Long waits in ED are certainly a contributor to excess deaths overall. Determining the size of that contribution requires further statistical analysis, tracking both the increase in ED waiting times and the number of excess deaths over time.

- Estimations – and the need for more data

The Department of Health publishes quarterly bulletins that look at various ED waiting time statistics. However, these publications do not include all relevant figures for each month. Instead, there is more detail about the final month in the quarter compared with the previous two.

For instance, the most recent publication – covering Oct-Dec 2023 – includes the total number of patients admitted to hospital following a visit to ED for December, but not for October or November.

However, two things the bulletin does make clear are that:

- ED waits for people subsequently admitted to hospital have risen significantly in recent years.

- Despite that, a significant proportion of such visits have for several years been over six hours.

Figure 4 – source: DoH bulletin on ED waiting times for Oct-Dec 2023

The table above shows that the median ED waiting time for patients admitted to hospital has been above six hours for a large majority of the period since April 2018.

By definition, this means that most of the time more than half of all admitted patients wait longer than six hours in ED – which, based on the EMJ published research, leads to extra/unnecessary deaths. That research states:

“A statistically significant linear increase in mortality was found from 5 hours after time of arrival at the ED up to 12 hours (when accurate data collection ceased).”

This means that, according to the data, longer waits result in more extra deaths, in a linear proportion, for waits of between five and 12 hours.

However, due to a lack of data, the researchers were unable to say whether or not this linear increase continues (or whether there is some other kind of increase, or no significant increase at all) for even longer waits.

- Bigger scale?

The research showed that waits of between six and eight hours led to one extra death in the following 30 days for every 82 patient attendances in ED. This rose to one extra death for every 72 attendances for waits between eight and 12 hours.

Do even longer waits result in a higher number of extra deaths? Well maybe – but also maybe not. The research published in the EMJ found a clear pattern in waits of between six and 12 hours, but lacked the data to say something equally concrete about waits of longer than that.

There is no guarantee that 12+ hour waits are effectively more dangerous than those of 6-12 hours because, for instance, a significant proportion of those cases could involve patients who are considered relatively low risk following triage – the fact that all cases here involve patients admitted to hospital notwithstanding – while those with more significant or simply more immediate health challenges are dealt with more quickly.

Furthermore, clearer findings about the relationship between 12+ hour waits in ED and mortality rates in the following 30 days would be useful, all things being equal. However, the path to that knowledge involves collecting more data, which itself is undesirable in the real world because it means a significant number of people waiting over half a day in emergency rooms.

FactCheckNI also discussed these questions with the RCEM, which was keen to point out that assumptions should not be made about areas where there is a genuine lack of data, adding:

“The evidence we use is limited to patients who are being admitted to hospital through emergency departments. There are (relatively) unmeasured deaths happening in other parts of the urgent and emergency care system and these will have got worse over the last five years; patients avoid seeking emergency care because they lack confidence, patients who are harmed by ambulance delays, and patients who discharge themselves or are discharged from emergency departments when they should be admitted. The operational pressures will also be causing deaths in these populations that isn’t measured.”

Overall, this is an interesting question for for Northern Ireland, because according to the latest ED bulletin:

“During December 2023, the median time patients admitted to hospital spent in ED was 14 hours 19 minutes.”

That means half of all people attending ED who were then admitted to hospital waited less than 14 hours, 19 minutes – and half waited for longer.