by Allan LEONARD for FactCheckNI (9 November 2017)

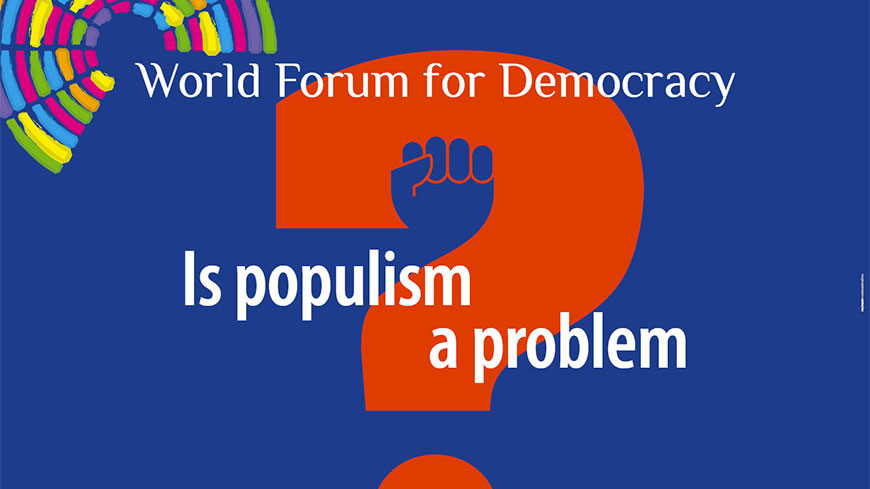

For the second year, thanks to Building Change Trust, which provides financial support to FactCheckNI, I was able to attend the annual World Forum for Democracy event in Strasbourg, France. This year’s title was “Is populism a problem?” and reflected upon the election of Donald Trump as US President as well as the surge of populist politics around the globe.

As it happened, I was able to spend all of the second day of the conference attending sessions on fact-checking: a panel discussion and two lab sessions on the topic.

The panel discussion was “From fake to facts: How to strengthen ties among research, policy and society to counter populism?” The premise was that in the face of the proliferation of ‘fake news’ and normalisation of uncivil behaviours in the public sphere, there is a demand for evidence-based resistance that could be strengthened through strategic partnerships among researchers, policy makers, and the media.

Mr Rinus Penninx (Professor of Ethnic Studies at University of Amsterdam) here spoke much of the framing of dialogue in society, and how facts are subordinate to such frames. He called for children to be taught more in schools about what happens in politics. Penninx criticised academics for not being more engaged in real world politics (i.e. going beyond theory to examining performance). Likewise, he said that politicians should have an interest in science; but both academia and politicians should remain independent of each other.

Mr Matjaz Gruden (Director of Policy Planning, Council of Europe) explored why some hang onto falsehoods, even after the facts have been presented to them. He suggested that grievances of non-belonging (alienation, disenchantment) presents opportunities for others to fill with beliefs. This underlined Penninx’s hypothesis of framing being more important than facts.

Ms Anna Krasteva (Professor of Political Sciences, New Bulgarian University) argued that the world of populist youth is not one of fake vs fact, but a selective use of facts and myths to bring a sense of cohesion amongst believers. She quoted Max Weber: facts and myths play the same role in community solidarity. Krasteva also made the argument that conspiracy theories provide a readier explanation for phenomena; “mediated, aestheticised, and glorified identities” are untouchable by facts; and individual identities can neither be verified nor falsified by facts. She depicted this as an illustration of a “David of Facts” vs “Goliath of Fake”.

Mr Tituts Corlatean (MP, Romania and MPA, Council of Europe) suggested using a local approach to combating fake news, with direct contact with people, asking them what they think about it and advising them how they can recognise it on social media. (Indeed, training in schools and local communities is a crucial dimension of our work at FactCheckNI).

Mr Yuri Borgmann-Prebil (Policy Officer, DG Research and Innovation, European Commission) described his organisation’s research programmes. MYPLACE looked at young people and how they may look at radicalisation.

Horizon 2020 consisted of three work programmes: exploring effects of inequalities among younger people; waning trust in public and private authorities; and identifying indicators and consequences of populism. He reminded the audience that the purpose of European Commission (EC) research is to provide evidence to inform (not determine) Directives and policy, and said that they would be exploring the effects of misinformation (fake news) in future programmes. (Coincidentally, shortly after the conference closure, the EC published a public consultation on the very topic.)

Ms Rosemary Bechler (Editor, OpenDemocracy) explained how it is impossible to have a debate in the United Kingdom about Brexit, because each side believes the other side is “completely deluded”. She said that British political and media culture is not conducive to a civic conversation; in parliament, politicians talk past each other while the media acts up the parties’ positions. But perhaps Bechler’s desire is not impossible, as she gave an example of a citizen’s assembly in Manchester, which included expert proponents on both sides and citizens were sincerely engaged, discussing the issues, and even some “enjoyed changing their mind”.

* * *

I had the responsibility of rapporteur for the lab session, “Fact-checking: Is it worth it?” (with audio podcast), which was moderated well by Mr Bertand Levant (International Organisation of La Francophonie). The format was two presentations, followed by two discussants, and finally a question and answer session.

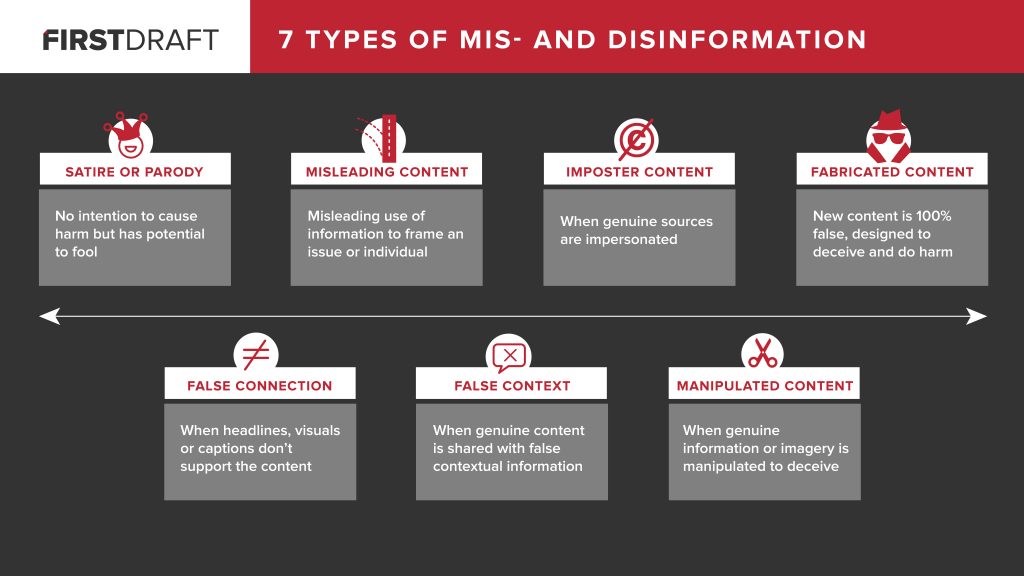

The first presentation was by Ms Marie Bohner, on the CrossCheck France project (which she served as coordinator). She described how CrossCheck France was launched in February 2017, to create a claim verification service for the French presidential campaign. The project had 37 partner news organisations, which investigated 64 claims and produced videos and infographics. Bohner defined the objectives of CrossCheck as going beyond a true-false dichotomy; they developed a typology of seven types of misinformation/disinformation:

She said that collaboration within the media sector for this project wasn’t obvious; some saw participation as a way of increasing competition, while others didn’t see the need for increased transparency. “But we saw it as something that was already online, these rumours, and that we needed to get out of our bubble,” Bohner explained, adding that local media partners increased trust with their audiences. An important lesson the project partners learned was that their reaching out to ordinary people on the ground — showing individuals how fact-checking works — resulted in direct engagement with those on both extreme sides of the political spectrum. Bohner saw this as a way of satisfying a public service mission of media organisations.

Mr Robert Holloway (Chair, Africa Check) described how Africa Check was established in 2012, as a UK-based non-profit organisation, but created a French-speaking subsidiary two years ago and are in the process of transitioning the business to Africa. Africa Check employ 15 staff full-time and operate in South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, and Senegal. It has fact-checked over 1,500 claims; the major theme is public health, but it also covers migration, economy, and weapons.

Holloway said that one of the positive things it did was to help get rid of certain contagious diseases. From 1998-2001, Nigeria had a rate of about 50 new cases of polio. Then in 2002 there was a rumour that vaccines were part of a conspiracy to make women infertile, and politicians did nothing to dispel the rumour; new cases of polio increased to 1,600 in 2006. A public information campaign helped reduce that number, but Holloway made the point that more than 3,000 people got polio because of unfounded rumours that were not checked by the media.

So for Holloway, yes, fact-checking is worth the effort.

Mr Jamal Eddine Naji (Director General, Audiovisual Communication, Morocco) was the first discussant to respond to the presentations. He mooted the apparent demise of professional journalism in his country, while arguing that journalism training should begin at the age of five: “Workshops on journalism don’t mean anything; [training] should be done in the field, in companies or elsewhere.” He added that local media have an obligation to present accurate data, to encourage citizens to seek out even more accurate data.

Mr Gotson Pierre (Editor, AlterPresse, Haiti) acknowledge the role that social media plays in the spreading of misinformation, but reminded the audience of the power of radio stations, which can be more prevalent in developing countries. Pierre also remarked that traditions of authoritarian behaviour can embed distrust of official institutions producing data and information, retarding the development of a fact-checking process (where does one go to get reliable data?). This has a strong effect on the operations of professional media, especially as guarantors of viable information.

As rapporteur, my three takeaway points of this lab session were:

- The innovative response of mainstream media to cooperate in addressing misinformation during an election campaign (but revert to competition thereafter?)

- The responsibility of public service by fact-checkers and journalists, while appreciating the political-legal environments in which they operate (freedom of press; authoritarian reprisals)

- The re-engagement between journalism and the public, which includes civic education and training programmes

* * *

The second fact-checking lab session that I attended was “Fake news: Does fact-checking work?” (with audio podcast), where a colleague, Paul Braithwaite, served as rapporteur. This lab was to look into examples of fact-checking methodologies to identify the most effective approaches in cracking down on fake stories.

The lab’s first presentation was about the non-government organisation, Union of Informed Citizens, based in Armenia. Its founder, Mr Daniel Ioannisyan, described its aims of using fact-checking journalism to increase public support for democratic values, human rights, freedom of expression, and political reforms. It seeks to promote facts for the wider population, disclose “the real face and narrative of propagandists and populists”, and build the capacity of free media.

The next presentation was a trio of speakers on the EUCHECK project. Ms Kate Shanahan (Head of Journalism and Communications, Dublin Institute of Technology) said that a real challenge for traditional media is for it to recognise that it is operating in a propaganda and disinformation-rich environment. She described EUCHECK’s purpose is to train a new generation to ensure that the public is well informed. Ms Carien Touwen (Senior Lecturer, Journalism Research, HU University of Applied Sciences, Utrecht) explained how EUCHECK consists of 15 journalism schools throughout Europe (within EJTA, which itself consists of 70 journalism schools in 28 countries). She defined the project’s desired outcomes for 2020 as being: (a) co-creation of fact-checking modules in journalism curricula in schools; and (b) establish fact-checking platforms at the national level. Touwen handed over the presentation to Georgia Oost, who explained how she and her classmates identified, researched, and published their fact-checked claim articles on a website, WTFact. The students also organised social media output, created databases, worked in a newsroom, visited in-person election events, and held a live fact-checking event:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NpzOM4BrA74

Mr Roman Dobrokhotov is the Editor-in-Chief of The Insider, which is an investigative newspaper that seeks to provide its readers with information about the current political, economic, and social situation in Russia. His presentation was a harrowing perspective on how Russian-linked misinformation campaigns are having a direct impact on people’s lives; he made a correlation with military battle lines in Ukraine.

“Fake news has become part of information warfare,” Dobrokhotov said.

He explained that there is a marketplace for the production of fake news. In addition to those hired to type up malicious content for dissemination on social media channels, Doborkhotov told us how opportunistic individuals will hire themselves out as actors of a sort, willing to say anything to camera, for a price. His organisation’s project, Antifake, tracked down such a person, who readily admitted to telling fabricated stories about receiving abuse by migrants in her town.

Dobrokhotov said that people do like to know how and when they are being deceived. What he noticed about the EU referendum campaign was the UK mainstream media did not/could not counter the scale of misinformation (N.B. Shanahan’s remark above on the misinformation environment). Dobrokhotov repeated the need to reach young people with fact-checking campaigns.

The first discussant was Mr Simas Celutka (Director of European Security Programme, Vilnius Institute for Policy Analysis), who said that debunking stories is not enough, and that we need to “strike at the core” of the problem of misinformation, about the aims and targets of all of the fake news: “If we don’t believe in our own way of life, then the populists will become more influential.”

The next discussant was Mr Gunnar Grimsson (Co-founder of Citizens Foundation), who spoke about the challenges of making fact-checking projects sustainable. As he saw it, it is easier for small groups of people to work together on an issue, because you more readily trust those that you’re working with; new dynamics emerge when scaling up operations. Furthermore, what is missing in some projects is an element of fun in participation, of either enjoyment or some personal gain; not everyone is a fact-checking nerd!

Grimsson added his voice to those who say that critical thinking skills need to be taught early, and crucially, with the internet in mind, “because waiting until age 30 is too late”. He also highlighted the importance of measuring the impact of fact-checking projects.

In the subsequent Q&A session, unsurprisingly there were many remarks made about the methodology of Russia-linked misinformation campaigns. The moderators, Mr Erdogan Iscan and Mr Conor McArdle, did well to ensure that there were no accusations levied against the Russian government or permit any form of uncivil discourse. Lest one though Dobrokhotov less than patriotic, he himself stated: “I am here to defend Russia and the best way to do that is to combat fake news.”

Doborkhotov also remarked that what is at hand here is a contest between pluralism and relativism: “If we divide ourselves into separate echo chambers, democracy dies.”